Sean Howe has written the book that pulls together all the major headline and backstage stories of the Vietnam-era antiwar movement and ties them together around the mysterious figure of Tom Forcade.

His Agents of Chaos: Thomas King Forcade, High Times, and the Paranoid End of the 1970s will certainly be considered one of the classic new sixties’ histories along with Judy Gumbo’s Yippie Girl: Exploits in Protest and Defeating the FBI, which came out in 2022.

Tom Forcade: Man of Many Moods

Tom Forcade was the mysterious, unsung former publisher of Underground Press Syndicate, the first nationwide network of underground papers from the Vietnam era. The underground press was the antiwar, independent, dissident press. He was the first underground press editor to obtain press credentials. He was a major drug dealer and founder of High Times magazine.

As Howe notes, he was “by 1975 at the intersection of multiple groups—radicals, journalists, and drug dealers—that were in the crosshairs of the government.”

According to people who knew him, he was a genius but totally nuts.

He was funny but vicious.

A lunatic and a visionary.

Narcissist and romantic.

Crazy, irrational, and self-contradictory.

“A dark cloud.”

And paranoid. Everyone agreed on that. A psychological report diagnosed him as having “Schizophrenia, Paranoid Type.”

Was he a CIA agent? No one was sure. Miami’s local underground paper, Daily Planet, observed that “Tom Forcade, depending on who you talk to, is either the grooviest revolutionary to come down the pike or a contemptible subversive who is wrecking the movement and is probably a police provocateur.”

Even Jack Anderson, the legendary investigative journalist and syndicated columnist, could only surmise that he was “a weird character with a black sense of humor” and an inclination to take Republican money if tempted.

Yippie Splits into Two Factions

My life intersected with his for one blinding flash of time, with the Yippies and Zippies in Madison, Wisconsin, and Miami Beach, Florida, during the Summer of 1972. It was the most surreal period of my almost three-quarters of a century of life.

The Yippies, who four years before had become myths in the minds of young Americans, were now embroiled in a bitter feud among leaders. The primary cause of the feud was disagreement with the amount of proceeds owed by Yippie co-founder Abbie Hoffman to Tom for sales of Abbie’s Steal This Book.

The disagreement had caused Yippie to split into two factions. The one led by Abbie and his Yippie co-founder Jerry Rubin represented the first-generation Yippies and their followers, including those who fought in Chicago 1968. The one led by Forcade represented the second-generation Yippies, those who had been too young for Chicago 1968 and were now ready to serve their country in Miami Beach 1972.

Tom had created the group as an alternative to the Yippies, claiming they needed to get out from under the shadow of Abbie and Jerry. He called them Zippies, “to put the zip back into Yip.”

The young protestors who came down to Miami Beach that summer, including me, for the most part had no idea there had been a split at the top of Yippie Central and didn’t care. At the campsite, Yippies and Zippies organized together, got high together, slept together, and just wanted to stop the war.

I Become Part of the Story

I became part of the story in May of 1972 when I broke up with a woman in Lansing (I know it’s a cliché but that’s what happened; stick with me), confronted my depression by hitchhiking into Madison to visit a friend, discovered the students had gone home for the summer, and was left not knowing anyone else in town.

Thanks to the local counterculture’s Crash Pad File of volunteer hosts, I found a place to crash with a writer on Madison’s underground newspaper, Take Over, who was also active with Madison YIP (Youth International Party).

The day after I arrived, Yippie Dana Beal was released from Dane County Jail where he had done nearly a year for marijuana possession. The next day, he hitchhiked into Madison with a pound of weed for the upcoming Smoke-In. I met him the next day.

We clicked immediately. We were both hyperactive, gifted political organizers, and—the clincher—from Lansing. Our friendship was destined. As we say in Yiddish, it was b’shert, meant to be. He was a few years older than me and a longer-time youth radical than I was so he saw me as a young him; in my mind, I was Robin to his Batman. To others, I was Dana’s friend and was immediately accepted into the inner circle of the Madison YIP community.

Dana Beal: Not Recognized in His Own Time

Dana has never received the recognition that is due to him. He would be a household name today, like Abbie and Jerry, if, during the Chicago riots, he hadn’t been in jail for another of his many drug busts.

Howe quotes one former Yippie as saying, “Tom sees Dana as sort of a junior varsity leader.” That’s not how the young people in Madison and Miami Beach saw him. He was a magnet of determination and commitment. At the Smoke-In in Madison, he delivered a speech he had rehearsed daily in his latest prison cell and his performance was flawless.

A few nights later, I was beat almost senseless by police in the civil disobedience that followed Nixon’s blockade of Haiphong Harbor. Dana’s lawyer paid my bail and took care of the legalities.

When I got out, I learned the Madison YIPs were planning to go to Miami Beach where both presidential nominating conventions were being held that summer. I rode down there with them.

In Miami Beach, Dana was the link keeping the Yippies and Zippies together as one. Fresh out of jail again, he hadn’t been forced to choose between Yippies and Zippies so both sides were vying for his support.

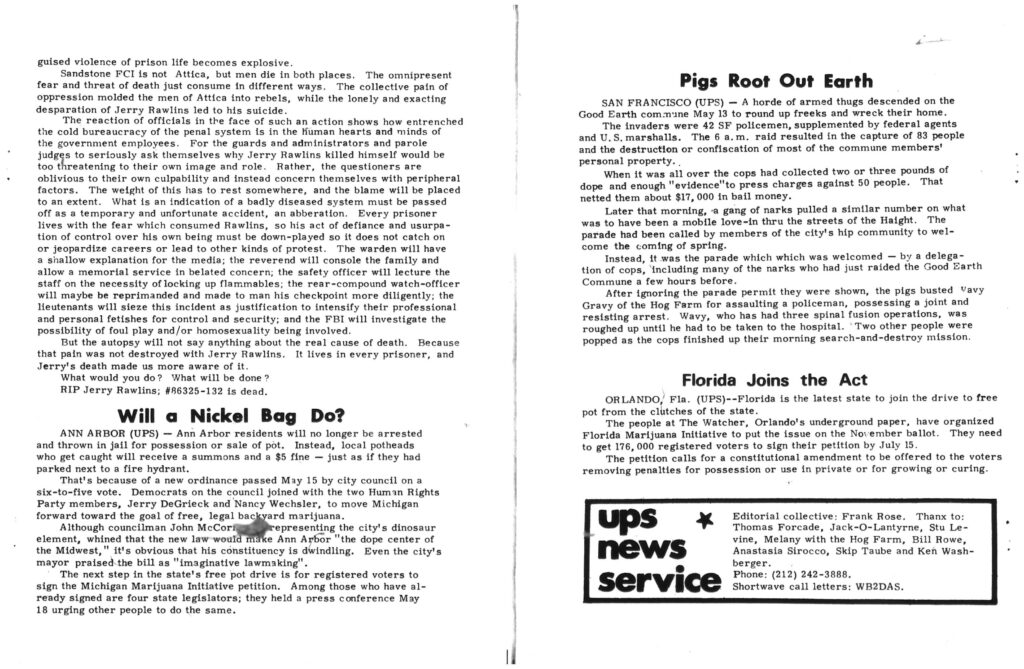

We stayed with Forcade at the Zippie House in Coconut Grove. I was welcomed into the inner circle, which included Tom and his friends. A thrill was working on the UPS member newsletter (see figure above). The underground paper where I worked in Lansing, Joint Issue, was a member.

Meanwhile, Tom moved constantly, whether he was writing, calling out instructions, producing and directing the guerrilla theatre demonstrations he financed, or provoking other movement groups.

Young People Unite with Old People to Secure Campsite

Occasionally he showed insight even if he didn’t get credit for it. Miami Beach was a largely Jewish old folks’ community. We young people were coming to town and demanding that the city provide us with a park where we could set up camp. Giving us a park would mean displacing the senior citizens who hung out there.

The right wing saw an opportunity. They dredged up memories of Chicago ’68 to instill fear in the senior citizens. It worked. Senior citizens began crossing the street when they saw a group of us approaching.

Tom realized we needed to begin doing outreach and gave Joyce Hodges and me $10 to do something. We began introducing ourselves to senior citizens’ groups. We allowed them to touch us. A young people-old people alliance began to emerge. We were given Flamingo Park as a campsite.

But somewhere along the way, Tom’s darkness began to snuff out my passion with the Zippies. I drifted away and became part of the Yippies. I’m pretty sure Joyce did, too. Yippie took ownership of senior citizen outreach.

The symbolic highpoint of the summer was Yippie’s “Wedding of the Generations,” which was held at Lummus Park on the Sunday before the Democratic Convention began. Joyce represented the young people. An old couple from Miami’s poor downtown Jewish community represented the senior citizens.

Jewish poet Allen Ginsberg acted as rabbi. Abbie recited a Yiddish poem he wrote on the plane down to Miami Beach called “Nixon Genug,” which is Yiddish for “Enough Nixon Already.” We voluntarily changed the slogan of credibility to “Don’t trust anyone over 35 and under 60.”

Harsh Ending to Tom Forcade Story

The book ends in November 1978 with Tom blowing his brains out. Abbie, who was at the time living life as an underground fugitive, writes, in a third-person Village Voice article, “The Fugitive and Tom had made their peace two years ago.” I was happy to learn they had reconciled but I wondered how it came to be.

Whatever you thought of Tom Forcade, he was a force of nature. He was someone who always knew he was going to play a major role in history and wanted to dress the part. I knew him for his two dress outfits: his solid black suit with black wide-brimmed hat and black shoes and socks; and his solid white suit with white wide-brimmed hat and white shoes and socks.

What lessons can we learn from Forcade’s story? For Howe, they change from time to time.

“But the one that seems to stick around the most, and the one that’s on my mind right now, is the idea that political movements need coalitions to work, and that internecine battles can be devastating. I think we live in a time, again, in which glib certainties are too plentiful, and that people need to listen to each other’s ideas and opinions.”

* * *

Ken Wachsberger is an internationally known author, editor, and book coach. He edited the landmark four-volume Voices from the Underground Series, called “the most important book on American journalism published in my lifetime.” His Independent Voices is the largest keyword-searchable digital collection of underground papers ever compiled. He may be reached for speaking or coaching at [email protected] or https://kenthebookcoach.com.

Image of UPS newsletter page courtesy of Sean Howe. Not surprisingly, Ken’s name is spelled wrong in the staff box.